Authors : Guteriano Neves and Bojamma Gandhi

Source: http://aitaraklaranlive.wordpress.com/2014/04/16/service-sector-in-timor-leste-challenges-and-impacts/

Service Sector Dominates Non-oil GDP

Types of Services in Timor

Banking and Financial Services

Telecommunication Industry

Wellness Industry

Travel Agencies

Management Consultancies

Challenges

Some Companies are of the opinion that some of the local companies lack business maturity as there is no business training by the Chamber of Commerce. Hence, business mentoring is required at least on due diligence, accounting and tendering process.

The high inflation rates, few jobs, trade imbalances, lack of clear State policies and laws and non-existent manufacturing sector threatens the economy and the business success of these companies.

Conclusion

Source: http://aitaraklaranlive.wordpress.com/2014/04/16/service-sector-in-timor-leste-challenges-and-impacts/

Introduction

Timor-Leste has been experiencing what is known as double-digit non-oil economic growth during the last five years. It is broadly agreed that this growth is boosted by expansionary fiscal policy, pursued by the Government. Without deeper exploration, one indicator of this growth can be observed in the expansion of service sector in Dili, specifically. As it is obvious, many new businesses are set up in Dili, such as hotel and accommodation, wellness services, management consultancies, banking and Telecom sectors etc. During the last three months, Department of Documentation, Analysis and Research of the Presidency of Republic conducted qualitative interview of Business owners across the sector operating in Dili, to find out the motivation of the business establishment, their experiences in doing business in Timor-Leste, input purchase, dealing with the Government, as well as their future plans. Based on these interviews, and deeper analysis on the nature and structure of the Timor’s economy we conclude that there is positive trend on the economy of Timor-Leste, and strong confidence on the domestic economy among businessmen who are operating in Dili. However, it is arguable that since most of the inputs are not generated in Timor-Leste, these businesses have not had a wider trickle-down effect on Timor’s economy.

Service sector is the biggest contributor for the non-oil GDP. According to the statistics from the Ministry of Finance of Timor-Leste, since 2004, more half of the non-oil GDP is from service sector and it continues to grow. In 2005 Service Sector accounts for 60.7% of non-oil GDP and in 2011, it was 59.4%. Looking deeper to sub-sector, there are three areas that are the biggest: public administration, retail and wholesale and real estate activities that dominate service sector in Timor-Leste in a given year.

Compare to agriculture, although it is believed to be the main source of livelihood of most Timorese, in term of its contribution to the GDP, it continues to decline. According to the most recent statistics released by the Ministry of Finance, in 2005, agriculture sector contributes 30% of Timor’s GDP whereas in 2011, it declined to 15.9%. The biggest decline took place in 2011, where agriculture sector decline by 5.7% compare to 2010. In total, between given period, agriculture sector decline 2.0% on the annual basis. Understanding this, one needs to take into consideration also that most of agriculture activities have not been commercialized; hence, it is not counted to the GDP. Manufacturing sector is experiencing the biggest growth rate in a given period by 15.1% growth rate in a given year, or grow by 2.16% every year.

The fact that Timor’s non-oil GDP is dominated by service sector is not unique to Timor’s economy therefore is seen as the positive trend to modern economy. At the regional level, according to the most recent report, released by the Asian Development Bank, since 1975, service sector already accounts for more than 43% of the GDP output in developing Asia, and in 2010, it accounts for more than 48% of the GDP output. As such, the growing of service sector in Timor-Leste is seen as the positive sign of modern economy. As stated in the proposed 2014 state’s annual budget, given that primary sector declines, and the growing of the manufacture sector, is seen as the positive trend as it moves from agrarian based economy to modern upper middle-income countries.

Although it seen as the positive trend, it is obvious that most of the most of the activities in the service sector takes place in Dili. Almost all hotels, restaurants, real estate activities, salons, banking are in Dili. This is due to the fact that by nature, service sector flourish in a place where middle class exists. Thus in the case of Timor, most of middle class are in Dili, and most of them are benefited from recycle of petrodollars. Secondly, Dili is the administrative centre where since 1999, most of international staff live and spend their money at, and now most of the public servants live. Due to this, service sector does not have wider impact for the national economy. Another concern is in term of labour share. Although it is the biggest contributor of the GDP, it is not the biggest employer. In Timor-Leste, is still considered that agriculture is the biggest employer. This trend is shared regionally, whereas although service sector is the biggest portion of the GDP, but in term of labour share, it is still lower than agriculture. According to the Business Activity Survey, released by the Department of National Statistic, in 2011, total employment in the private sector was 58,000; out of which, 30% are in the Construction, retail and wholesale, as well hotel and accommodation. Given the importance of service sector in Timor-Leste’s economy, it is critical to understand the dynamic that involves in this sector.

There are various types of service that operate in Timor, especially in Dili; some in large-scale, and some in smaller scale. The following are some of the booming services that operate in Dili.

- Public Administration

- Hotel and accommodation

- Salon, spa and gymnasium

- Banking and Financial Service

- Security services

- House-keeping services

- Renting – commercial space and houses and apartments, vehicles

- Travel agencies

- Professional services

- Financial services

- Marketing, advertisement and printing services

- Health services

- Private schools

- Auto repair workshops

- Insurance providers

In general, the Hotel Industry has improved over the last 10 years. Many new hotels and restaurants have opened up during the United Nations Organisation’s (UNO) time here and after, creating an affordable and quality oriented segment. Although there was a worry that UNO’s departure will have wider impact on this industry, our interview shows that UNO’s departure from the country has not had damaging effects, as their usual clients are Embassies, Non Government Organisation’s (NGO), International Organisations, business persons, the Government and few tourists. According to some hotel owners, the departure of UN is positive for Timor’s economy, as UNO’s presence is always associated with the conflict and war.

The restaurants and the housing accommodation have taken a hit in their business with the departure of International employees of UNO. A very few popular restaurants have consistent business.

We learnt in our interviews, that investments made range from 2 millions up to 8 million USD. In term of access to land, most hotels own the land the hotel building is on, but some continue to rent and lease the land. Most businesses have met and in some cases have even exceeded expectations.

The profitability of hotels varied with some popular hotels operating at a consistent profit and some have seen a slump in profits with the opening of new hotels in Dili. The locals own very few of the big hotels that cater to International standards.

The inputs that the hotel industry requires in terms of building raw materials, furniture, cutlery, decorative items, and kitchen equipment are sourced from neighbouring countries like Australia, Indonesia and Singapore. Even in some cases, spare parts of kitchen equipment, maintenance and trained technician to fix it in case of a breakdown are not available in the country. Challenges also lie in terms of access to technology for e.g. inconsistent and slow Internet connections hamper the reputation of the hotel especially with the Business people. Sometimes, basic vegetables and fruits, dairy and meat products are not available in the market for months, making it hard for the restaurants to serve a dish in its entirety. If some places do have the inputs that are in shortage, the prices shoot up immediately.

Most vegetables and fruits are locally procured. Some hotels have designated families in the districts to grow vegetables and fruits for them. However, this does not guarantee yearlong uninterrupted supply of consumables. Most recently, the prices of products that are being imported have gone up. Many restaurants have increased their prices of food and drinks by 2 to 3 USD.

Most ground level and mid-management employees are Timorese, with Managers being Internationals. There is professional and on job training provided to all the recruits. Every establishment has Human resource policies, which support promotion, leadership and constant training.

Banking and Financial Sector consists of five banks – three private – Caixa Geral de Depositos (CGD)/BNU from Portugal, Mandiri Bank from Indonesia, Australia New Zealand Bank (ANZ) from Australia and New Zealandand two State owned Banks – Banco Nasional Comericio and Banco Central Timor-Leste, and two money transfer companies – Western Union and Moneygram. BNU has been operative in Timor-Leste since the Colonization and suffered discontinuation during the Indonesia occupation, while Bank Mandiri, Central Bank and ANZ Bank were established during the UNO administration period.

When the commercial banks were established, initially all of them operated as deposit banks, and not retail banks. In the last 3 to 4 years, Personal and corporate lending were introduced by some banks as the country’s stability improved, and the laws pertaining to investment and commerce were created. Due to the fact that Timor-Leste is endowed with natural resources, mainly – oil and natural gas, the country is attracting various types of investors.

Due to the increasing users of banking systems and services, ANZ has started diversifying their products and services to increase their customer base. Services such as personal loans, Internet banking, cheque drop offs, customer service via telephone, cash-in cash-out programs have been introduced. Mandiri Bank is issuing visa cards.

Banking Institutions have invested in capacity building in the form of Intellectual property via brining in experts from other countries to train Timorese on all aspects of Banking. The Banking Experts also provide Advisory and guidance to the Government on Finance and sustenance.

Although there are many improvements, the future looks optimistic with various projects underway; the financial institutions face quite a few challenges. There is a strong feeling of growth and security, which helps the Banks attract and invest in lending to more Investors.

After a decade of Independence, Timor-Leste’s telecom industry has seen a surge in the year 2013. When Indonesia retreated from the country, it also destroyed about 70% of the physical infrastructure that existed. Even through the 2006 crisis, telecommunication sector continued to show growth with mobile telephone sector growing steadily. There is a steady but slow growth in the Enterprise Consumer market for both Telephone and Internet. So far, the Capital Investment varies from 40 to 50 million USD, with more investments planned for the year 2014.

Portugal Telecom created a subsidiary called Timor Telecom (TT) in 2002 and was initially granted an exclusive license in the market until 2017. In March 2012, however, an agreement was reached between the government and TT to end its monopoly earlier than planned. A tender was subsequently launched for two mobile licences. By 2013 the two new operators – Telkomsel from Indonesia and Telemor from Vietnam launched their respective mobile offerings and the market is rapidly changing due to competition mainly on pricing.

Although, the telecommunication prices in Timor-Leste is now diversified and competitive, the fact remains that the charges for services are among the highest in Asia, in comparison with the telecommunication and internet prices in India for example.

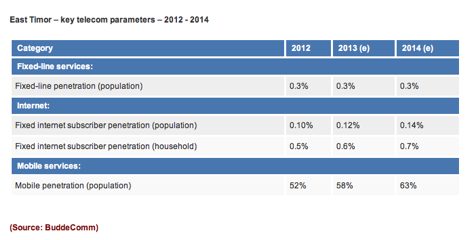

According to the recent report published by marketresearchreports.com,[1]After recording huge annual growth rates over a number of years from 2006 onwards, by the start of 2014 the country’s mobile subscriber base had increased rapidly in a short period of time and penetration was close to the 60% mark. Fixed-line network expansion did not see the same growth, with fixed tele-density down around 0.3%. The Internet market data is hard to find. However, it remains concentrated in Dili. Fixed broadband service subscribers continue to remain extremely low. The advent of mobile broadband Internet access provided a boost to the Internet sector.

Report Highlights:

- After surging in the 2008/2009 period, the East Timor mobile market grew by around 30% in both 2010 and 2011

- However, total mobile subscriber growth was ‘flat’ in 2012, ahead of the licensing and launch of two new operators

- The Timor Telecom monopoly had officially ended in April 2012 and the two new operators were licensed in July 2012

- In the newly competitive market, mobile subscriber numbers had reached an estimated 700,000 coming into 2014.

- In sharp contrast with the mobile market, both fixed-line subscriptions and internet usage in its various forms remained especially low, with only modest growth likely in the short term

- The government was also in the process of setting up a new independent regulatory authority for the sector. See more at: http://www.marketresearchreports.com/paul-budde-communication-pty-ltd/east-timor-timor-leste-telecoms-mobile-and-internet#sthash.rdkhAfVQ.dpuf

[1]http://www.marketresearchreports.com/paul-budde-communication-pty-ltd/east-timor-timor-leste-telecoms-mobile-and-internet. Excerpts from the report- However, total mobile subscriber growth was ‘flat’ in 2012, ahead of the licensing and launch of two new operators

- The Timor Telecom monopoly had officially ended in April 2012 and the two new operators were licensed in July 2012

- In the newly competitive market, mobile subscriber numbers had reached an estimated 700,000 coming into 2014.

- In sharp contrast with the mobile market, both fixed-line subscriptions and internet usage in its various forms remained especially low, with only modest growth likely in the short term

- The government was also in the process of setting up a new independent regulatory authority for the sector. See more at: http://www.marketresearchreports.com/paul-budde-communication-pty-ltd/east-timor-timor-leste-telecoms-mobile-and-internet#sthash.rdkhAfVQ.dpuf

For Operational activities, the human resource used are mainly the locals. The companies make use of the International Labour Organisation’s program to provide employment in the villages to the locals on short-term basis to perform manual labour, while the technical and managerial roles are performed by Internationals.

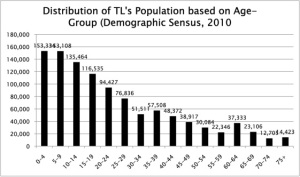

Although challenges persist, some companies have exceeded expectations with some of their yearly goals achieved. They get a sense of business security after the Presidential and General elections in 2012. The Companies have plans and goals to introduce more technology to diversify the market further. As Timor-Leste is a new market with an increasing number of young populations and enterprise set ups, the market absorption for various products is good.

There are number of salons, spas and gymnasiums run both by the locals and internationals. The businesses are doing well with most costumers being the locals. There was slight dip in the first six months of the year after the departure of UNO, but the market has picked up since.

The quality of the newly opened salons, spas and gymnasiums are of International standards. Compared to the rest of Asia, for e.g., Bali and Thailand, these services are very highly priced, and the quality is not up to the mark of the price being charged.

A common problems encountered by the businesses were physical security threat of the buildings due to stone throwing and burglary. Some establishments have moved to Timor Plaza for a ‘worry free’ business environment and have seen great results.

| Daily flights | Sriwijaya | Air North | Silk Air |

| Destination | Bali and Jakarata | Darwin | |

| Weekly twice / thrice | Singapore |

The motivation behind establishing travel agencies is that in the period between 2006 and 2007, the agency services were limited, and the consumers were very high given the UNO presence in the country. At present the consumers are mostly private corporates, locals and Government Institutions.

Timor- Leste faces its own share of challenges in the travel segment too. Timor-Leste is not a member of IATA. Therefore, there is no International representation of the country. As the nearest Office is in Bali and Singapore the communication between the agencies and IATA is delayed. The costs of telecommunication, electricity, Internet and building rent are high. All these elements increase the price of the tickets considerably and the cost is passed on to the customers.

Flights such as Merpati and Sriwijaya are blacklisted in the European market forcing tour groups to fly via Singapore, increasing the costs significantly. Europeans do not want to fly to Indonesia due to the high risk factor, and there are no daily flights to Singapore. Lack of public transport increases the price of the tour, as renting cars becomes the only option.

Most travel agencies have stopped working with the Government related institutions as they have faced issues regarding delay and non-payment of dues in the past. Numerous complaints have been registered at the Finance and Treasury and some cases are pending for over three years.

Many travel agencies also face issues in terms of discipline. In most cases the agencies need to have an International staff member as backup. Most locals hired do not speak Portuguese or English making language a barrier and hiring more difficult.

In spite of the overwhelming challenges future prospects are encouraging. Group tours are predicted to pick up next year with Europeans, mainly Germans and Portuguese visiting Timor-Leste for adventure Tourism. This is a result of one the travel agency participating in a Travel Fair in Europe. A cruise ship from Australia will resume tourism activities here next year. Operations to Timor-Leste were halted after the 2006 crisis.

The travel agency fraternity is of the opinion that the services in Timor-Leste would be better if the Government invests in obtaining an IATA membership. Many travellers from the country transit via Bali frequently, so a special arrangement could be made to avoid paying visa fees for travellers arriving from Timor-Leste. Slight face-lift for the existing guest houses/Pousada, regulating entry fees into touristic spots, making the beaches crocodile free zones would attract more tourists. Participation in various International travel fairs would help in spreading the country’s tourism aims.

The motivation behind setting up Management, Law, IT firms are because of the market needs and requirements, common official and working languages and projects and contracts with the Government and existing clients. Costumers are from Timor-Leste, Singapore, Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

Since 2005, there have been many Management Consultancies of various functions being set up in Timor-Leste. These setups have seen the sector expand and are attracting more establishments, as there is a sense of business security.

There are some fundamental issues that are still present that needs attention from the Government authorities. The Consultancies are of the opinion that the requirement to have a Resident Director who is a local does not seem to work, as the shareholders find it difficult or nearly impossible to trust an outsider to be in a decision making position in a privately held company.

For a business set up, the International shareholder has to get the Company registration documents (certificates, by-laws) endorsed by the Timor-Leste Embassy in the home country. Although there is legal provision for Timorese Diplomatic representative in any country to endorse documents of this nature, only the Timor-Leste Embassy in Portugal is equipped to so.

Although the laws of the country are adapted from Portugal and are in the Portuguese language, many students continue to study law in Indonesia. Once back in Timor, they struggle to speak the official languages on a professional level and to understand the existing laws of the country.

The country is slowly showing business maturity and the various improvements that the business set ups have seen in the last 12 years are a proof to that, other than the new development projects that are stemming up. Business opportunities continue to expand. Despite the improvements, there are some common challenges that most business set-ups continue to face, which needs to be addressed.

A year back, the timeline for Business registration process was more than 6 months. With the introduction of ‘Serve’ program by the Government, the timeline has been reduced to 4 weeks. The Notary Office is composed of two notaries. They do not have a back Office to provide secretarial assistance. Therefore, the process to obtain signatures from the Notaries is prolonged. There are no standard templates for documents; hence, the format and content of documents are ever-changing.

Across most businesses the locals are hired more than Internationals for Administrative and manual jobs. The Internationals continue to perform Managerial roles because there is a shortage of skilled Human Resources at the Managerial level. Many inputs required to run businesses here have to be procured from other countries, as there is no large-scale manufacturing sector in the country. Timor-Leste depends on Indonesia, Australia and Singapore for most of its inputs.

Due to the long history of Colonization, and the subsequent Occupation, displacement of people, and the legal uncertainty with regards to the land, people do not feel secure about their investments in the country.

The double-digit inflation in the country increases rent, hiring services, living and imports costs while driving up the operational costs. ‘Opportunity costs’ are also high due to frequent travel requirements and non-availability of daily flights.

The process to obtain associated Public Services such as Work VISA, driving license and public transport are cumbersome. Corresponding VISA or resident permits are not issued for the period of the license.

The Official languages of Timor-Leste are Tetun and Portuguese and the working languages – English and Bahasa Indonesia. Most business people from Asia and Pacific do not speak the Official languages, which has created a huge language barrier. There is a need to build English-speaking skills to enable a thorough business environment.

Some businesses also face the threat of physical security as they have suffered property damage because of stone throwing, vehicle theft and drunken youth bothering the customers. Many a businesses are hesitant to conduct business with Government related institutions as they have faced issues with payment delay, and sometimes non-payment.

The Telecom Companies continue to face Operational, Legal and Human Resource issues. One of the main issues faced in the land compensation during the infrastructure establishment around the country. On many instances, more than 2 or 3 groups lay claim on the same piece of land. Hence, the companies end up spending 3 times the projected cost to erect antennas and towers. This is due to the non-existence of Land Law. There is always an uncertainty that the next ruling Government might change its policies and revoke current agreements (E.g., Timor Telecom’s monopoly agreement). Due to the fact that Timor-Leste does not have a large-scale manufacturing sector, all the inputs have to be procured from other countries. This creates delay in the implementation of the plan, and increases the cost considerably.

There is no legal framework for security collateral for the lending program. Due to the fact that the Land Law is still not been promulgated, many civilians lay claim to land without legal documentation, which makes it impossible to lend without legally endorsed collateral.

Some Companies are of the opinion that some of the local companies lack business maturity as there is no business training by the Chamber of Commerce. Hence, business mentoring is required at least on due diligence, accounting and tendering process.

Conclusion

Timor-Leste is experiencing a confident, slow and steady trend in the growth of its service sector, as it dominates the Non-oil GDP. With the decline in the primary sector, the manufacturing sector is growing by 2.16% every year. The 2012 General and Presidential elections that were democratically successful and peaceful, has created an impression of political maturity and stability in the country.

There are both large and small scales set-ups in this sector with Telecom being the largest. Service sector is centralised to Dili due to the concentration of trade, employment and State Administration.

The UNO’s departure did not have tremendous damaging impacts on the economy. It can also be viewed as economy back to normalcy. A large number of International community still live in Dili and contribute to the service sector considerably.

Despite the various challenges, most businesses see positive prospects for this Industry, as many new establishments are being set up. Most hotels are occupied with Business people who are looking to find new opportunities in the emerging economy.

When the Land Law is promulgated, there would be an increase in the banking activities, as pledging legally endorsed collateral would become a norm. The market will witness further diversification of services and introduction of new technologies.

There is also a huge scope for improvement in the telecom sector. If the existing telecom companies decide to provoke a price war, the consumers will enjoy lower fees for services, more products and better access.

The country needs to find creative approach towards Tourism. Tourism Industry has an immense potential. If Tourism activities picks up, it will certainly provide a big boost to the service sector, and overall the economy of the country.

An efficient and well-equipped public administration system would go a long way to enable a convenient business registration and other related public services. This seems to be the biggest bottleneck across all sectors.

There is a need to bridge the language barrier to facilitate both the Portuguese and the English-speaking investors.

***END***